Using involvement in group discussions for (self-) assessment and learning

Last updated on 10th December 2022

(this blog post is freely downloadable as a Word doc and as a PDF file)

I recently gave a talk on "Therapist drift: black heresy or red herring?". Although that was the title, the talk rapidly segued into an exploration of the current state of psychotherapy and what we might do to improve our results. I argued that an excessive focus on comparing different types of psychotherapy (e.g. CBT, psychodynamic, interpersonal, behavioural, and so on) has directed us away from a potentially more productive area - researching why "Some counsellors & psychotherapists are more helpful than others" and what we can learn from these significant differences. One issue that I discussed in some detail is the recently emerging research on the importance of therapist interpersonal skills when assessed not by self-report, but by observing actual behaviour in challenging situations. The slide below lists four fascinating, relevant research studies:

I have already been exploring and have written (and am continuing to write) about Tim Anderson's work (e.g. the first three research papers listed on the slide above) - see, for example, "Truly excellent therapists have 'grace under interpersonal pressure': fascinating new research". What I want to talk a bit more about though in today's post is the fourth study listed on the slide - Schottke et al's paper "Predicting psychotherapy outcome based on therapist interpersonal skills: A five-year longitudinal study of a therapist assessment protocol", with its abstract reading "Objective: In the past decade, variation in outcomes between therapists (i.e., therapist effects) have become increasingly recognized as an important factor in psychotherapy. Less is known, however, about what accounts for differences between therapists. The present study investigates the possibility that therapists' basic therapy-related interpersonal skills may impact outcomes. Method: To examine this, psychotherapy postgraduate trainees completed both an observer- and an expert-rated behavioral assessment: the Therapy-Related Interpersonal Behaviors (TRIB). TRIB scores were used to predict trainees' outcomes over the course of the subsequent five years. Results: Results indicate that trainees' with more positively rated interpersonal behaviors assessed in the observer-rated group format but not in a single expert-rated format showed superior outcomes over the five-year period. This effect remained controlling for therapist characteristics (therapist gender, theoretical orientation [cognitive behavioral or psychodynamic], amount of supervision, patient's order within therapist's caseload), and patient characteristics (patient age, gender, number of comorbid diagnoses, global severity, and personality disorder diagnosis). Conclusions: These findings underscore the importance of therapists' interpersonal skills as a predictor of outcome and source of therapist effects. The potential utility of assessing therapists' and therapists-in-training interpersonal skills are discussed."

If you go to the wonderful resource that is ResearchGate, you can join up for free and get subsequent free access to the full text of Schottke's paper. I did this a while ago, but I was stumbling around the internet yesterday (it was a Sunday!) trying to get access to more details of the questionnaire that was used to assess Therapist-Related Interpersonal Behaviours (TRIB). I couldn't find the relevant information on Henning Schottke's ResearchGate page and I was in the process of emailing him directly, when I decided to chase up more information on Simon Goldberg, an obviously English-speaking co-author on Schottke's paper. I gained access to more and more fascinating research & information. I glanced at all publications on Simon's ResearchGate page and blow me, but there was a freely downloadable Online-Appendix to their paper which gave full details of their TRIB assessment questionnaires. Gold dust!

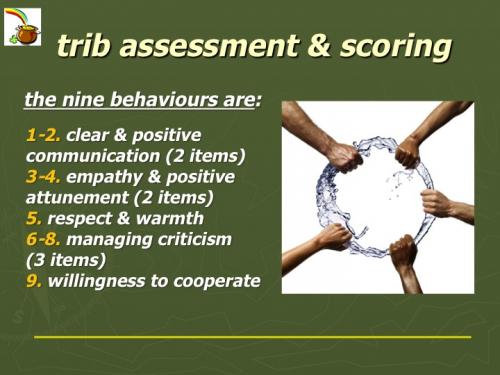

The relevant TRIB questionnaire is the one that was used to assess group interactions:

Now here's the more recent juice from yesterday (and it took a while to put these together) - firstly helpful descriptions of what constitutes poor and what constitutes excellent behaviour as rated with the TRIB-G, available both as a Word doc and as a PDF file, and secondly the TRIB-G questionnaire itself, available both as a Word doc and as a PDF file. For therapists and would-be therapists, this information provides rich material for assessment by oneself and, probably more importantly, by others ... with the obvious next step of identifying behaviours where one wants to improve and going through cycles of deliberate practice to achieve this - see, for example, this article on "The making of an expert" for more on this. But more broadly, as a therapist one can use many types of group meetings to observe and work to improve one's interpersonal behaviours.

When using the TRIB-G, it's probably helpful to know that in Schottke's study the average total score by the 42 assessed trainees was 27 ... in other words, their average score for each of the 9 items was 3. These are trainees who had already completed a 5 year Master's degree in psychology and who were so interested in becoming psychotherapists that they had enrolled on a further intense 5 year postgraduate training programme. This suggests to me that a score of 3 is likely to indicate a moderate amount of competence in the area being assessed. The standard deviation was 4.85, showing that with a normal distribution, 29 of the trainees scored between about 22 and 32 on the scale (approximately between 2.5 and 3.5 per item). Half a dozen or so of the 42 scored less than 2.5 per item (it went as low as a shocking 1.25) and half a dozen or so scored more than 3.5 per item (it went as high as a very impressive average of nearly 4). The main thing when scoring the TRIB-G is probably to be consistent. What I personally have done is to assume initially that the person I'm scoring is moderately competent and start them at a score of 3 for a particular item. I then mark them lower than 3 if they seem weak in the area, and mark them higher than 3 if they seem strong. I use half points too, so may well score someone at say 2.5 or 3.5. Knowing that with the 42 trainees assessed in the Schottke paper, their total scores ranged from 12 (1.25 per item) to 35 (nearly 4 per item) ... I try to be fairly "wide scoring" in my readiness to drop to 2 or rise to 4 on my assessments.

If one is using the TRIB-G as a feedback tool, it's worth highlighting that ideally it's likely to form part of an ongoing discussion. Helpfully giving and receiving feedback is a big challenge. Do look at the seven suggestions listed in the post "Some suggestions for giving and receiving helpful feedback". Note this seven-suggestions-on-feedback blog post is downloadable both as a Word doc and as a PDF file. It includes the quote from Casselman & Daughtry "Criticism is driven by the frustration and fears of the giver, not from the needs of the recipient. The underlying assumption is that the recipient somehow "should know better" and needs to be set straight. The implied message is that the recipient's intentions are questionable, that there is something wrong with the recipient that the giver of criticism knows how to fix. In criticism, the problem is all in the recipient. In contrast, feedback has an air of caring concern, respect, and support. Far from being a sugar cookie, feedback is an honest, clear, adult to adult exchange about specific behaviors and the effects of those behaviors. The assumption is that both parties have positive intentions, that both parties want to be effective and to do what is right ... Another assumption is that well-meaning people can have legitimate differences in perception. The person offering the feedback owns the feedback as being his reaction to the behavior of the other person. That is, the giver recognizes the fact that what is being offered is a perception, not absolute fact."

A couple of final comments ... firstly it's worth noting that the TRIB-G was used to assess interpersonal behaviours in a group discussion about a film clip. In a group with a more directly "therapeutic" focus, there are other aspects of interpersonal behaviour that are probably also important. Examples include the ability to personally go deeper into emotions at times and to help others do the same (see, for example, the "seven levels" of the "Experiencing scale") and the ability to "titrate" the "temperature" of the group (see, for example, the slides in "Group facilitator style & outcome"). Awareness of these kinds of "guide posts" for more helpful emotional work can be useful whether one is in a facilitator role or simply being an experienced, engaged & caring group member. Secondly it's useful to note that helpful interpersonal behaviours are NOT just for therapists. Far from it, helpful interpersonal behaviours are hugely and much more extensively relevant to pretty much all of us. I suspect that the TRIB-G is particularly relevant in assessing how well one functions in primarily a care-giving role. Obviously there is more to being a good parent, good partner, or good friend than how we are as care-givers. However this role is central to how we are in these relationships ... while also acknowledging the importance of other qualities too like humour, perseverance, inquisitiveness, joy, and so on. However do look at the TRIB-G questionnaire. How do you reckon you score on it (or ... even better ... how do others reckon you score you on it)? Would you be more helpful as a manager, a friend, a parent if you scored better? What can you do about this? This is a rich area to explore.

(this blog post is freely downloadable as a Word doc and as a PDF file)