Recent psychedelic research: what are the risks?

Last updated on 24th November 2019

"The conventional view serves to protect us from the painful job of thinking." J. K. Galbraith

"Although a bad LSD trip can be extremely frightening and distressing, psychedelics overall are among the safest drugs we know of. When the ISCD expert panel were rating LSD and mushrooms (which contain psilocybin) by our 16 criteria, they both scored either 0 or 1 in everything apart from specific and related impairment of mental functioning. It's virtually impossible to die from an overdose of them; they cause no physical harm; and if anything they are anti-addictive" David Nutt, professor of neuropsychopharmacology & international drug expert.

I have written four previous blog posts in this sequence - "Recent psychedelic research: an introduction", "Recent psychedelic research: their use in psychotherapy (1st post)", "Their use in psychotherapy (2nd post)", & "How do they work?" . In subsequent posts, I'll look at "Recent psychedelic research: Their use in the general population", "Re-mining personal experience" and "Recent psychedelic research: further exploration". This post however is about risks involved in using psychedelics and I would like to make three points about this. One is to highlight their surprising level of comparative safety. A second is to contrast the care taken when using these substances in traditional sacred/healing rituals around the world ... or when administering them in medical settings ... with the potentially considerably more risky practice of casual recreational use. And thirdly I will make some comments about ways of reducing these risks.

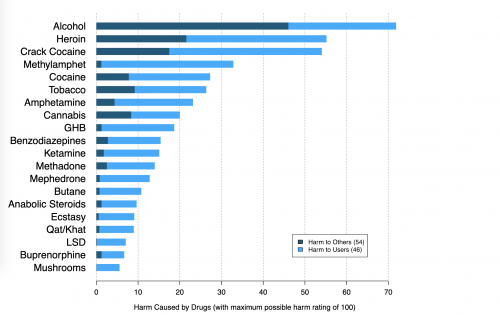

So first - as the above Professor David Nutt quote from his excellent book "Drugs without the hot air", highlights ... classical psychedelics (the 5-HT2a receptor agonists DMT, LSD & psilocybin) are remarkably safe. Don't misunderstand me here, psychedelic drugs can produce very powerful, disorientating & potentially dangerous psychological effects ... but physically and overall, they are surprisingly safe. This is well illustrated in the following chart comparing the carefully assessed comparative dangers of 20 widely used legal & illegal drugs:

This chart is also given in the Wikipedia article on David Nutt (who I'm proud to say read Medicine at Cambridge with me) and Wikipedia goes on to comment: "He is a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, Royal College of Psychiatrists and the Academy of Medical Sciences. He holds visiting professorships in Australia, New Zealand and the Netherlands. He is a past president of the British Association of Psychopharmacology and of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. He was the recipient of the 2013 John Maddox Prize for promoting sound science and evidence on a matter of public interest, whilst facing difficulty or hostility in doing so. He is past president of the British Neuroscience Association and current president of the European Brain Council." The evolving scientific clarification of relative drug harm is covered in the 2010 Lancet paper "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis", the 2015 Journal of Psychopharmacology publication "European rating of drug harms" and most recently the 2018 Int J Drug Policy's "A new approach to formulating and appraising drug policy: A multi-criterion decision analysis applied to alcohol and cannabis regulation" with its emphasis on developing state controlled ways forward that steer a helpful middle road between frank prohibition and a free-for-all decriminalisation. And if you're surprised by where alcohol appears on the relative harms chart above, more recent research highlights that it's even more devastating than was appreciated when the chart was put together - see last summer's blog post "Alcohol: it's more damaging than we realised".

So this was the first point I wanted to make about the risks of psychedelics - that in terms of direct physical damage to users, damage to non-users, and costs to society - these drugs are very safe compared with alcohol & tobacco. However the second point I want to make is to contrast the care taken when using these substances in traditional sacred/healing rituals around the world ... or when administering them in medical settings ... with the potentially considerably more risky practice of casual recreational use. Carbonaro & colleagues from John Hopkins put out an online survey to ask about psychedelic users' "worst 'bad trip'". The results were reported in their 2016 paper "Survey study of challenging experiences after ingesting psilocybin mushrooms: Acute and enduring positive and negative consequences" with the abstract commenting "Acute and enduring adverse effects of psilocybin have been reported anecdotally, but have not been well characterized. For this study, 1993 individuals (mean age 30 yrs; 78% male) completed an online survey about their single most psychologically difficult or challenging experience (worst “bad trip”) after consuming psilocybin mushrooms. Thirty-nine percent rated it among the top five most challenging experiences of his/her lifetime. Eleven percent put self or others at risk of physical harm; factors increasing the likelihood of risk included estimated dose, duration and difficulty of the experience, and absence of physical comfort and social support. Of the respondents, 2.6% behaved in a physically aggressive or violent manner and 2.7% received medical help. Of those whose experience occurred >1 year before, 7.6% sought treatment for enduring psychological symptoms. Three cases appeared associated with onset of enduring psychotic symptoms and three cases with attempted suicide. Multiple regression analysis showed degree of difficulty was positively associated, and duration was negatively associated, with enduring increases in well-being. Difficulty of experience was positively associated with dose. Despite difficulties, 84% endorsed benefiting from the experience. The incidence of risky behavior or enduring psychological distress is extremely low when psilocybin is given in laboratory studies to screened, prepared, and supported participants."

Gosh ... why would anybody want to risk experiencing these kinds of reactions? Well actually the authors comment that "A substantial majority of participants (84%) rated that they benefited from the challenging portions of their sessions. Almost half (46%) endorsed that they would want to repeat their chosen session and all that had happened in it, including the difficult or challenging portions of the session." Very intriguing. The median number of psilocybin sessions reported by these users was 6 - 10, and the survey specifically asked about the worst of their experiences, yet still more than 8 out of 10 respondents said they had benefited and nearly half would want to repeat this "worst trip". So, as with life more generally, difficult experiences may well turn out later to have been challenging learning opportunities. However "2.6% behaved in a physically aggressive or violent manner and 2.7% received medical help. Of those whose experience occurred >1 year before, 7.6% sought treatment for enduring psychological symptoms. Three cases appeared associated with onset of enduring psychotic symptoms and three cases with attempted suicide."

Now it's all very well putting this in perspective and pointing out, as the authors do, that "The incidence of psilocybin toxicity is extremely low relative to other drugs used non-medically. For instance, in 2011, emergency room mentions of problems (in the USA) with psilocybin alone (83 mentions) were only a very small fraction of mentions for heroin alone (10,309 mentions), cocaine alone (9828), and marijuana alone (9711)." And of course, these psilocybin emergency room figures are hardly even a pinprick when compared to the explosion of damage produced by alcohol ... the leading cause of death for 15-49 year olds worldwide. However, even if damage caused by psilocybin and other classic psychedelics (DMT, LSD & mescaline) is just a pinprick, it can still hurt badly if you or someone you know are one of the few to suffer the pinprick.

The research group at John Hopkins have given this serious thought as their 2008 paper illustrates - see "Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety" with its comment "The most likely risk is overwhelming distress during drug action ('bad trip'), which could lead to potentially dangerous behaviour such as leaving the study site. Less common are prolonged psychoses triggered by hallucinogens. Safeguards against these risks include the exclusion of volunteers with personal or family history of psychotic disorders or other severe psychiatric disorders, establishing trust and rapport between session monitors and volunteer before the session, careful volunteer preparation, a safe physical session environment and interpersonal support from at least two study monitors during the session ... Persisting adverse reactions are rare when research is conducted along these guidelines." For abbreviated and full versions of this paper, see this page on TripSafe.org.

The 2008 John Hopkins paper is cautious in its approach to keeping psychedelic interventions safe. This is great, but it's advice from the experience of one centre of excellence rather than the evidence-based fruits of a series of practice A v's practice B randomised controlled trials. Carefully run psychedelic research trials are blossoming and state-of-the-art practice will evolve ... but the John Hopkins model is a very good start-off point and TripSafe makes this advice easily accessible. There are many other sources of advice on trip safety on the internet. Examples include "How to use psychedelics", Michael Pollan's book-linked list of resources and the huge information trove at "Erowid.org". And there are also classic print resources like "The psychedelic explorer's guide: Safe, therapeutic, and sacred journeys". At least until further research emerges "personal or family history of psychotic disorders or other severe psychiatric disorders" make sense as exclusion criteria ... although the latter part of this exclusion may obviously be waived when using these materials in controlled therapeutic interventions. Interactions are likely with other (legal) psychiatric drugs. There are potentially big problems with sourcing good quality psychedelics and their legal position is obviously currently a big issue as well. "Set" and "Setting" seem especially important when working with psychedelics, so how someone approaches a psychedelic journey, the environment they take it in, the support they have from others, and other factors are all very important to consider. A little like approaching any potentially very challenging experience in our lives, we're stupid if we don't gather information, pay attention to advice from those who have had the experience before us, and carefully weigh the pros and cons. If all of this is taken into account, psychedelics are much safer than government legislation and media foolishness might have us believe.