Personal social networks (1st post): Dunbar's 5-15-50-150 model

Last updated on 27th August 2025

Relationships are immensely important for both our health and our wellbeing ... for how long we live, our resilience to psychological stress, and for our levels of happiness & life satisfaction. This is crucially relevant for pretty much all of us. The post "Strong relationships improve survival as much as quitting smoking" clearly links the state of our personal social networks to how long we're likely to live. Last autumn's major paper "Social support and protection from depression: systematic review of current findings in Western countries" states "Evidence is overall highly consistent and supports the notion that social support is an important protective factor against depression." Exploring the same territory, the 2016 paper "Factors contributing to depressive mood states in everyday life: a systematic review" reported "A review of the literature suggests that poor sleep, negative social interactions, and stressful negative events may temporally precede spikes in depressed mood. In contrast, exercise and positive social interactions have been shown to predict subsequent declines in depressed mood." Interestingly a further 2016 paper - "Impact of functional and structural social relationships on two year depression outcomes" - highlights that relationship quality is likely to be more important than quantity in protecting against depression. And study after study has underlined the crucial importance of relationships for wellbeing - see, for example, the posts "Friendship: science, art & gratitude" and "The balanced measure of psychological needs scale".

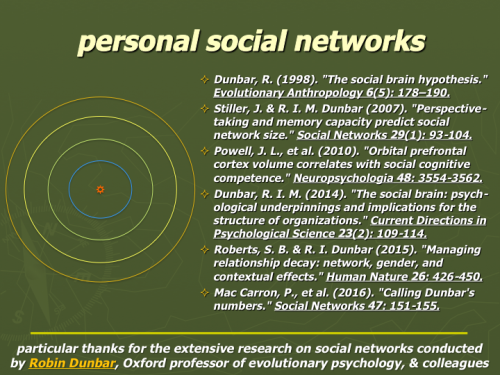

One of the best models for understanding personal social networks emerges from the deeply intriguing work of Robin Dunbar, Oxford professor of evolutionary psychology. He has written a number of popular books including "Human evolution: our brains & behaviour", "The science of love and betrayal" and "How many friends does one person need?: Dunbar's number and other evolutionary quirks". Dunbar's website links to over 240 of his academic publications. The two slides below (and two in the next blog post) provide an introduction to some of his ideas including the well argued thesis that our personal social networks can helpfully be seen as made up of a number of layers (with ourself at the centre), each larger layer increasing in number of constituent members by a factor of about three when compared to the layer inside it.

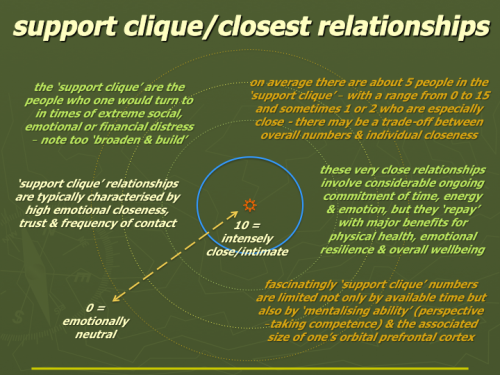

The innermost layer is often rather awkwardly labelled the "support clique" and it represents our closest relationships. As a rough estimate, the support clique typically includes about 5 people (0 to 15 or so). It may well be structured to involve 1 or 2 really close relationships and an additional 4 or 5 close relationships. We interact with these people regularly, typically at least weekly, and they tend to take up a good 40% of our social time budget. Interestingly these support clique relationships can be identified both by the time involved in them and by the degree of emotional closeness that characterises them. The support clique usually includes the people one would turn to in times of extreme social, emotional or financial distress. But the very close relationships of the clique are not just about support in times of trouble, they are also very much about good times too - people who we really enjoy being with and who help us flourish. Our children may be in this very close relationship group and so too can some of our pets - see "Basic psychological need fulfillment in human-pet relationships and wellbeing" & "Pets as safe havens and secure bases".

Fascinatingly, with all these personal network layers, it isn't simply a matter of "the more the better". Excellent support & wellbeing are probably best provided by very approximately 5 in our support cliques. Many more than this, and the time demands involved in maintaining relationship quality typically mean we start to lose some emotional closeness. Significantly less than 5 (or several of the 5 living at distance) probably means we're more vulnerable in crises and that our wellbeing is lessened. We're all unique, so we should treat these generalisations cautiously. What works best for us will vary from person to person, with our gender, our characteristics and also with the stage of our lives. Individuals tend to show differing & somewhat consistent social network activity patterns - see, for example, Saramaki et al's paper "The persistence of social signatures in human communication". It seems women often tend to particularly value fewer conversation-based relationships and men more numerous activity-based connections - see, for example, "Managing relationship decay: network, gender and contextual effects" & "Women prefer dyadic relationships, but men prefer clubs". However there may well be more variation between individuals than genders, with some men deeply valuing conversation-based emotional closeness, and some women being activity-focused in relationship maintenance. Empathizing/systematizing differences may be of importance here - see "Testing the empathizing-systemizing theory in the general population: occupations, vocational interests, grades, hobbies, friendship quality, social intelligence, and sex role identity".

Stage of life is also important ... so adolescence, romantic relationships, raising young children, building career success & moving into retirement all present different challenges & opportunities for the size & use of our "social time budget". How easily we are able to develop & maintain really close relationships seems also to be affected by our ability to mentalize - "mentalization can be seen as a form of imaginative mental activity that lets us perceive and interpret human behaviour in terms of intentional mental states (e.g., needs, desires, feelings, beliefs, goals, purposes, and reasons)." This ability (like most abilities) is partly genetic, partly learned from our parents & those around us as we grew up - see "Translating child development research into practice: can teachers foster children's theory of mind in primary school?" - and partly developed (and we can continue to develop it) over the course of our lives.

The next post in this sequence - "Personal social networks: the sympathy group & the full active network" - discusses the further, less emotionally close, but still very important layers of our personal relationship networks.

(This current post "Dunbar's 5-15-50-150 model" can be downloaded as a Word doc or as a PDF file, and the two slides in this post & the two in the next can be downloaded to make a two-slides-to-a-page Powerpoint handout.)